Tours

Original Emergency Department, Trauma Room C

In the early hours of June 12, 1963, civil rights leader Medgar Evers was rushed to this room after being shot in the driveway of his nearby home.

On the same night, one floor above this room, Dr. James D. Hardy performed the first human lung transplant, starting on the evening of June 11 and finishing during the early hours of June 12. Dr. Martin Dalton, a surgeon from Dr. Hardy's team, left the transplant operation to help the trauma team try to save Evers' life.

Tragically, the single bullet from a high-powered rifle had done too much damage, and by 1:30 a.m., Evers was dead. National outrage over his assassination would become a pivotal moment in the fight for civil rights, not only in Mississippi but also around the world.

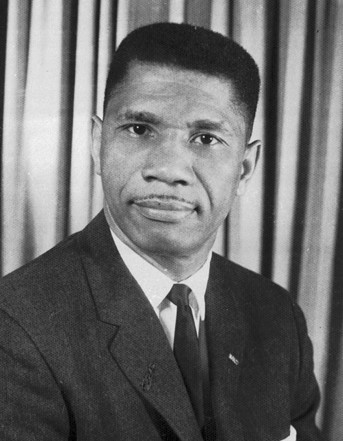

Medgar Evers, Civil Rights Leader

Medgar Evers, a prominent civil rights activist, was a key figure in the fight against racial segregation and injustice, serving as the NAACP's field secretary in Mississippi and advocating for voter registration, economic boycotts, and investigations into crimes against Black people.

Photo courtesy of MDAH.

On the night of his assassination, Evers returned home after a meeting with NAACP lawyers. As he was getting out of his car and walking toward his house, he was shot in the back by a white supremacist named Byron De La Beckwith. The bullet from a high-powered rifle entered Evers' back and passed through his body, shattering into pieces.

After being shot, Evers collapsed in his driveway, but he managed to drag himself about 30 feet toward his front door before he lost consciousness. His wife, Myrlie Evers, and their children found him on the ground.

Trip to the Emergency Room

Evers was loaded into a neighbor's station wagon and rushed to the University Hospital emergency room. Surgical residents attempted to save his life through emergency procedures, including a thoracotomy. Still, Evers died from severe lung injuries and blood loss, according to Dr. Martin Dalton, who had been working with Dr. James Hardy on the world's first lung transplant in the surgical suite one floor up from the ER.

Evers was immediately given treatment. Incorrect reports have persisted for decades, saying Evers was at first turned away from UMMC's ER because UMMC didn't accept African American patients, but this is not accurate. UMMC has served the state's entire population since its opening day in 1955, though areas of the hospital were once segregated.

In her book, For Us, the Living, Myrlie Evers-Williams, Medgar Evers' widow, recounts her conversation with family friend and noted Jackson physician Dr. Albert Britton. Dr. Britton had stayed with Evers the entire time Evers was being treated in the UMMC ER. Dr. Britton did not have privileges to practice at UMMC, so he could not participate in life-saving efforts, but he assured Ms. Evers that the doctors had done everything they could possibly do to save his life.

Aftermath

Evers' assassination shocked the nation and became a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. His funeral in Jackson drew thousands of mourners, and he was later buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. The fight for justice took years; Byron De La Beckwith was tried twice in the 1960s, but both trials ended in hung juries. It wasn't until 1994, over 30 years later, that Beckwith was convicted of Evers' murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Evers' assassination highlighted the dangers civil rights activists faced in the Deep South and galvanized the movement for racial equality in America. His life and legacy continue to inspire generations in the struggle for civil rights.

Sources and more information

Evers-Williams, M., & Peters, W. (1996). For us, the living. University Press of Mississippi.Rucker AJ, Baden MM, Llewellyn M, Pappas TN. The Assassination of Medgar Evers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022 Jan;113(1):366-371. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.06.075. Epub 2021 Jul 31. PMID: 34343472.